‘But Kate, why make something about the future? The coral’s dying, the trees are dying, the animals are dying and we are going to die very shortly. End of story!’ Marco, aged 10.

In my 35 years of making theatre work with children, I’ve been buoyed up by their enthusiasm, their openness and their optimism. We have often made works about their imagined futures. The worlds they create are weird and wonderful, full of possibility and hope. But in the last five years, I’ve noticed a marked dystopic timbre to not only the content of these artworks, but in the children’s dispositions. They’re worried about the future.

They know about climate change and they know the adults around them are also anxious about it. They hear about (and sometimes experience first-hand) increased bushfires and floods and they are, very understandably, scared. And the older kids are frustrated and angry with governments who seem to be denying it and/or doing nothing about it. It’s been inspiring to witness young people taking matters into their own hands, namely the Strike4Climate marches, initiated by two Year 9 students here in Victoria. There’s a swell of positivity – these young people are feeling like they are being seen, heard and most importantly listened to by many adults. Unfortunately though the adults in power are making it clear they are not listening, protesting instead that children shouldn’t be activists and need to be in school rather than the streets. So the positivity and hope for a better future is in danger of being quelled.

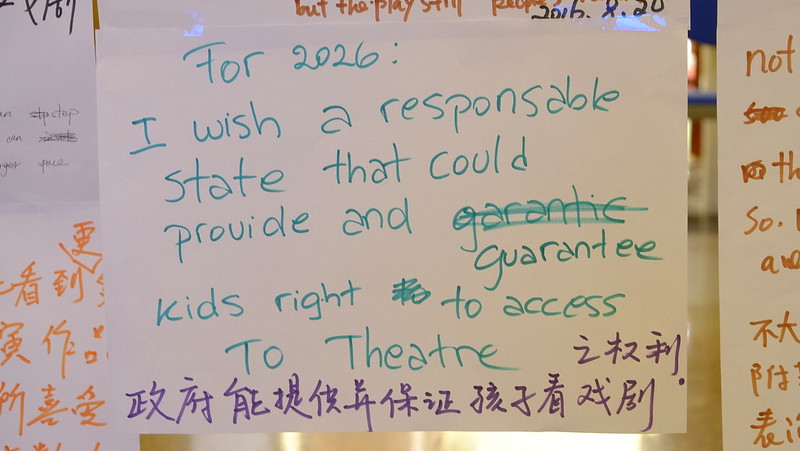

How do we keep the hope and optimism alive? How do we ensure that young people’s voices are being heard and valued, in their classrooms and in their communities?

A number of teachers I have worked with have voiced a fear of discussing the realities of the future with their students. This is understandable, particularly with younger children; there are issues of mental health at stake. Renowned educator and environmentalist, David Sobel recommends ‘no tragedies before Grade 4’ (Sobel 1996), and I’m with him there. But for Year 5/6s, they are more developmentally ready to cope with some challenging realities. And very savvy themselves… they can tell if we’re skirting around an issue. It’s much better to acknowledge that global warming is certainly happening and we are at a precarious place in the history of Planet Earth.

Bronwyn Hayward, a leading thinker in the field in the area of children and ecological citizenship gives us a rather daunting list of skills and qualities that young people will need to create a sustainable future: critical thinking skills, the ability to reason, reflect and communicate clearly; resources to enable mobilization across time and place, and restraint to live within material limits, as well as the virtues of empathy and tolerance, co-operation and moral reasoning, determination and courage. (Hayward 2012)

This is where art making, specifically theatre, is very helpful – many of these skills and qualities are developed through the highly collaborative act of making theatre.

Many things are unknown – we have to accommodate this sometimes very uncomfortable feeling of not knowing and maintain our openness and flexibility. These states of being: openness to change, uncertainty and resilience, are central to drama games, central to the creation of theatre, central to life itself. Through the process of exploring character and different viewpoints, drama develops empathy and critical awareness. And we as teachers need to be modelling openness and flexibility: by really listening, by acting on the kids’ suggestions, by doing what we say we will do and by having a genuine creative conversation. All the time aiming not to survive, but to thrive.

In instigating and investigating the authentic collaboration involved in creating theatre together, artists and teachers are modelling what the future can be. In walking the talk and making big changes in our own environmental and civic behaviour, young people can see that we are committed in our own actions as well. Child psychologists Gill Valentine and Roger Hart suggest strongly that children deal much more effectively with difficult and sometimes sad issues concerning the environment when supported by adults and older peers (Valentine 2004; Hart 1997). And having these highly engaging creative opportunities in schools ensures that young people have the avenues to speak their truth – the content may be confronting and difficult for teachers and parents, but the kids’ passion and determination are truly inspiring.

Exploring local actions, and making changes for sustainability at that level, works really well with kids. Looking at changing waste disposal at the school, having edible gardens and extending out to work with partners and community to look after waterways and parks that are close to the school are also excellent projects that give the kids a sense that adults also want to instigate change. Schools that engage with their local communities become much more profound sites of learning, exploring and developing the connection of community to democracy. And involving art making as a tool of inquiry and expression of understanding and change within these local actions works a treat!

Having the possibility of making local changes gives all of us hope. Thinking globally and acting locally still rings true.

In a recent project in Melbourne’s north, I worked with a team of artists, school students and local council over a number of weeks to imagine the best possible use for some local unused land. The children were deeply engaged in the task and collaborated in a way I have never experienced before. They had brilliant, highly pro-environmental ideas for the space, and presented these creative, practical and achievable plans as a participatory arts event with the local community. Local council, which viewed this kid-led process as an authentic consultancy, is (as I write) putting the ideas into hard landscaping in the space. The part of the event that was the most popular with the kids and adults was the theatrical enactment of animal culture in this little pocket of suburbia. This drama was deeply affecting and witty at the same time; comments from audience members afterwards focused on the kids’ passion for the animals’ wellbeing and the clarity of their message.

For me, their engagement, passion and courage was uplifting. It fuels me to continue to find ways to listen to and support their brilliant ideas. All power to them. The future is theirs.

References and further reading

- Valentine G 2004, Public Space and the culture of childhood, Aldershot , Ashgate, p 105

- Hart R 1997, Children’s participation : The theory and practice of involving young citizens in community development and environment care , London, Earthscan, p 65

- Hayward, B 2012, Children, citizenship and environment : nurturing a democratic imagination in a changing world, London : Routledge, 2012.

- Sobel D 1996, Beyond Ecophobia: Reclaiming the Heart in Nature Education, Orion, Barrington MA

Biography

Kate Kantor has worked for over thirty years as a director, teacher, maker and actor in performance, film and installation work, both nationally and internationally. Her practice is strongly collaborative, and is situated in a wide variety of contexts and communities. Kate has a keen interest in young people’s agency around social and environmental issues. She has a Diploma of Education and Master’s degree in Arts Education and has worked for many years as a lecturer in performance and arts education at Victoria University. Much of Kate’s work has been around children and their relationship to the natural world, particularly through her role as the Artistic Director of The Return of the Kingfisher Festival at CERES for many years, and more recently as Director of Kids’ Collaborations at Polyglot Theatre. Kate is now doing a PhD at University of Melbourne focused on young people’s hopeful, creative and contributive strategies around environmental issues.

Published 6 February 2020